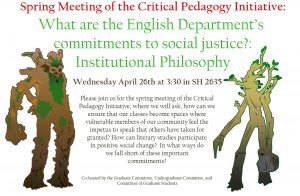

When we began the Critical Pedagogy Initiative in Fall 2016, we envisioned a progression from department specific issues outward to larger issues of the institution. Our third and final meeting of the year asked the question, “What are our Department’s commitments to social justice?” As you can see from our opening remarks, this question is institutionally relevant and focuses developing pedagogical strategies for application in our contemporary political moment.

When we began the Critical Pedagogy Initiative in Fall 2016, we envisioned a progression from department specific issues outward to larger issues of the institution. Our third and final meeting of the year asked the question, “What are our Department’s commitments to social justice?” As you can see from our opening remarks, this question is institutionally relevant and focuses developing pedagogical strategies for application in our contemporary political moment.

To address both of these aims, the development of pedagogical strategies and a clearer understanding of the department’s position toward social justice in the classroom, we structured this meeting around three scenarios. We split into smaller groups to respond to the scenarios, and then shared our responses with the larger group in attendance for discussion. Before this meeting, we had solicited scenarios and situations that would help us discuss the challenges of negotiating politics and affirming difference in the classroom. Graduate students responded with multiple scenarios, and we chose three that reflected the following recurring “thematic” situations:

- Students deny politically charged facts.

- Students assert misogynist beliefs.

- Students use racist phrases.

Scenario 1 – Denial of Politically Charged Facts

1st Example: A Teaching Associate has a student who is intensely conservative (at least politically). This student was amazingly vocal during the second meeting (the first substantive session) of his Climate Fiction class last Spring. In his opening comments (he was the first student to speak that day), he denied that climate change was happening and critiqued Dipesh Chakrabarty (a renowned Postcolonial historian) for citing a liberal philosophy (on a very benign point). It was a disaster in terms of student dynamics–the students who had read the piece carefully and were more politically liberal were sniggering behind his back and the Teaching Associate himself was thunderstruck. The Teaching Associate explained that other students chimed in with their thoughts on the reading, and that the session ended well despite this denial.

2nd Example: During a discussion section of Minority Literature (English 50) which focused on the novel “No No Boy” by John Okada, a student said that the attack on Pearl Harbor was justification enough for the internment of Japanese Americans, the historical event that backgrounds the novel. This student claimed that military strategy and the need to defend the United States was the reason for internment and discourses of Yellow Peril, despite the class’s emphasis on understanding how these acts of internment were motivated by racism.

One respondent suggested trying to turn this scenario into a teachable moment, to look at it as a space for different points of view. However, others pointed out that there is a limit to what can be permitted in the classroom. Openly hateful language should not be tolerated. Another participant felt it was important to make sure that the single dissenting voice is not heckled, to prevent students from feeling ostracized.

Other respondents felt this was an opportunity to help the students think through the formulation of their own ideas. For example, someone suggested tabling the discussion on whether climate change is real, and in the next class meeting, providing a space for the student to present his take on why climate change is real. There was a sense that setting this issue up as a debate could be problematic and lead to heated exchanges.

Scenario 2 – Outright Misogyny, Racism, or Homophobia

1st Example: During another discussion section of English 50, a teaching assistant facilitated a conversation about Chester Himes’ novel “If He Hollers Let Him Go.” A student says that a woman that the main character imagines raping, “was asking for it” because of her actions and the way she was dressed. The student said that despite the fact that the main character “obviously” shouldn’t rape this woman, the woman was acting in a way that made this student feel she was soliciting sexual violence.

2nd Example: While discussing a William Carlos William poem called “The Housewife” in an English 10 section, a student referred to the woman in the poem as a slut. When asked why he used this term to describe this woman, the student’s explanation played into what he envisioned “a slut” would look like. The poem describes the woman in erotically tinged terms, and the student referred to her as a slut.

Participants overwhelmingly felt that remarks such as “she was asking for it” do not merit space in the classroom (or elsewhere) because they can and do actively harm others in class. A response like the one above is inappropriate because it actively does violence. Other respondents supported this stance, and agreed that in this example it would be important to shut down openly sexist talk. One respondent affirmed that we are on a college campus, where sexual assault happens regularly, and where there are likely victims of sexual assault in our classrooms. This lived reality ties in to our belief that words can and do harm people, and that our responsibility to vulnerable students is not one we can take lightly.

We discussed pedagogical strategies for handling these kinds of scenarios, beginning with the understanding that we should not try to make students feel “stupid.” Although one suggestion was to have students teach other students by asking whether they agree or disagree, we realized that this could put the burden of explanation on students who are already vulnerable or marginalized. Although it is likely in these scenarios that other students will step in or offer their opinions, we agreed that the responsibility should not be placed on other students.

Professors and graduate students also suggested using syllabi as a way to negotiate these situations. We can rely on statements we made on a syllabus, regarding certain boundaries that shouldn’t be crossed. For example – “I encourage you to share your opinion, but direct comments at ideas and not at people.”

Scenario 3 – Unintentional Racist or Prejudiced Language

1st Example: On the first day of class this quarter, a professor in an upper division English course asked students to introduce themselves with their names and the best thing they read over break. One girl (clearly very awkward in general) went into a long spiel about the funny signs she saw in Japan, including “chocorate” for chocolate. The professor didn’t know what to do – the whole point of the exercise was getting people talking on the first day, so she didn’t want to shut her down, but obviously it’s not good. The professor tried to redirect and moved on.

2nd Example: What do you do in the moment when students employ stereotypes without thinking? For instance, when they try to criticize racism but make racist comments in doing so. Sometimes this takes the form of a student using language from the text that is not acceptable for everyday speech, such as saying “Negro” or “colored person” in class.

We shared these scenarios for future thought, but did not have time to discuss our responses to them. In the time remaining, we turned to these broader questions:

What are our expectations for each other when faced with similar scenarios?

What criteria should we consider, if we had time to think before facing these scenarios?

Responses:

- “Always be kind.” Try to encourage other students to be kind as well.

- Try not to turn to “targeted” students. Similarly, avoid placing the onus on students who identify with the position at stake.

- Don’t take it as a given that liberalism of students will win through.

- Point out that certain terms are just not used anymore, without overmoralizing.

- Try to build in exercises that help us to have more tools (like 7 minute debate for next class. Or write personal essays on their own positions).

- It’s ok not to entertain wrong answers.