What do you expect students to know when they enter your classes?

What do you hope students know when they finish your course?

How does this differ when teaching majors, non-majors, or both?

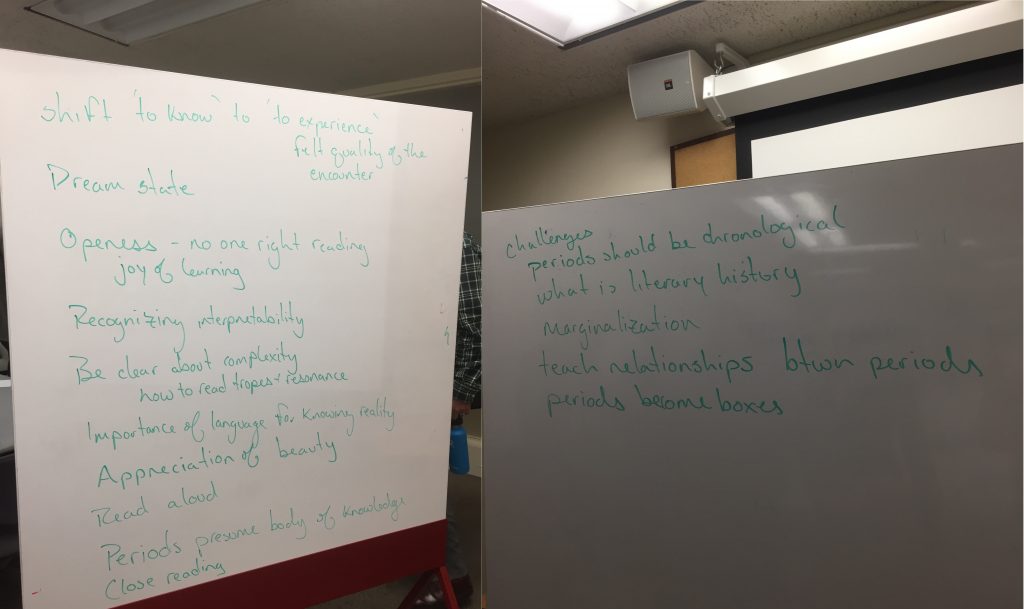

While our first meeting focused on the qualities of good teaching in general, our winter meeting negotiated the rocky terrain and dreamlike horizons of what, specifically, makes English unique. In addition to equipping our students with a particular body of knowledge, we strive, as Kay Young explained, to create shared dreamstates around texts. We help heighten the felt quality of the encounter with literature. It follows that, as Kristy McCants said, we emphasize openness– we are not teaching our students how to find the “right reading,” but that instead there is joy in learning. If we can teach our students how to recognize interpretability, we can reach our larger goal of embracing complexity, as Julie Carlson does, and not oversimplify the reading experience. Similarly, participants agreed on the importance of learning how to read tropes and resonance, and the related importance of language for knowing reality.

Bill Warner and Enda Duffy debated whether language and literature helps to engage reality or appreciate the aesthetic. Others did not see these pursuits as mutually exclusive; the work we do in the classroom brings literature to life in a way that can influence the world.

In addition to considering our aspirations for the English major, we discussed certain challenges with the organization of our curriculum. Many are invested in maintaining periodization as an organizing structure both because it is logical and because it leads students towards important fields they might not otherwise encounter. One challenge with this system stems from the fact that students do not always study these periods in chronological order because of the constraints of the quarter system, class scheduling conflicts, transfer student needs, and other reasons. Why order classes chronologically if they will not be taken in chronological order? Another challenge is that this system reproduces historical marginalizations and excludes some contemporary, important writers that don’t fit in an established field and time (for instance, Toni Morrison might not come up in the period courses required for English majors, although she is often taught in elective and gen ed English courses).

We can engage with these challenges by foregrounding literary history itself in our curriculum; what is literary history and why is it studied, and why do we even order literature around English in the first place? What are the historical and current reasons for doing this? Maite Urcaregui suggested that we teach the relationships between periods rather than the periods themselves, so that the periods become bridges not boxes. With this structure, history remains an important part of the curriculum but is framed through collaboration and questioning rather than holding its place as a framing device for the English major. This method of structuring the curriculum would also allow classes to be tailored around concepts and questions rather than historical periods, and would allow instructors the freedom to teach topics rather than be bound by date restrictions.

We can engage with these challenges by foregrounding literary history itself in our curriculum; what is literary history and why is it studied, and why do we even order literature around English in the first place? What are the historical and current reasons for doing this? Maite Urcaregui suggested that we teach the relationships between periods rather than the periods themselves, so that the periods become bridges not boxes. With this structure, history remains an important part of the curriculum but is framed through collaboration and questioning rather than holding its place as a framing device for the English major. This method of structuring the curriculum would also allow classes to be tailored around concepts and questions rather than historical periods, and would allow instructors the freedom to teach topics rather than be bound by date restrictions.

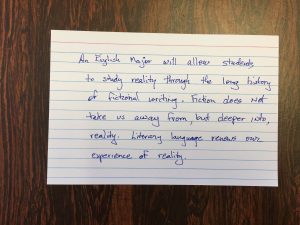

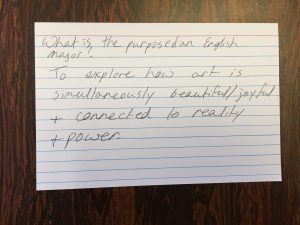

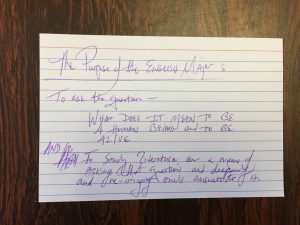

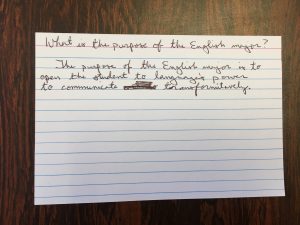

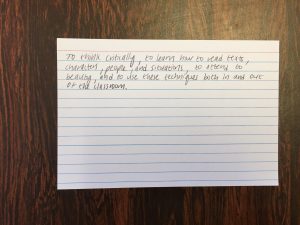

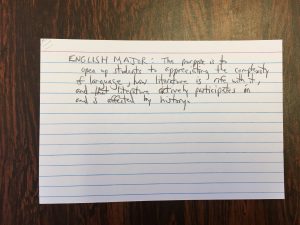

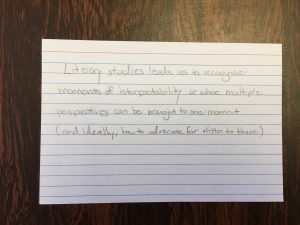

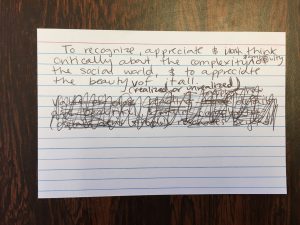

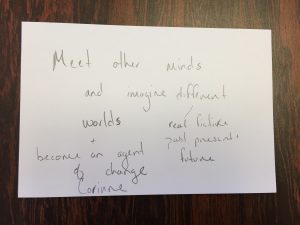

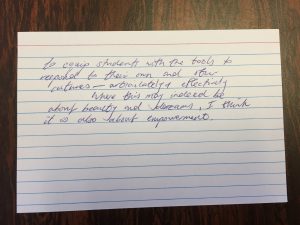

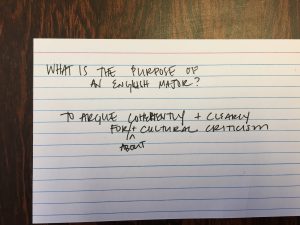

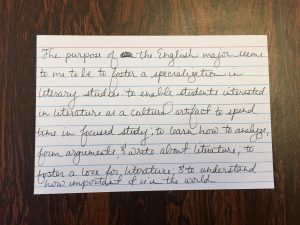

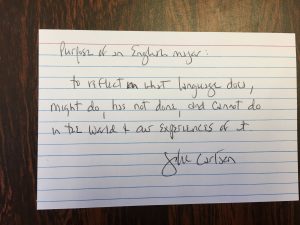

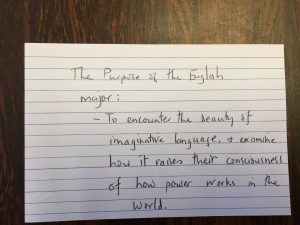

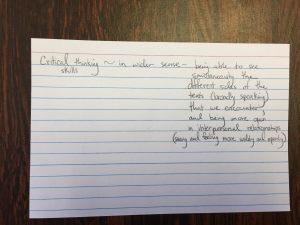

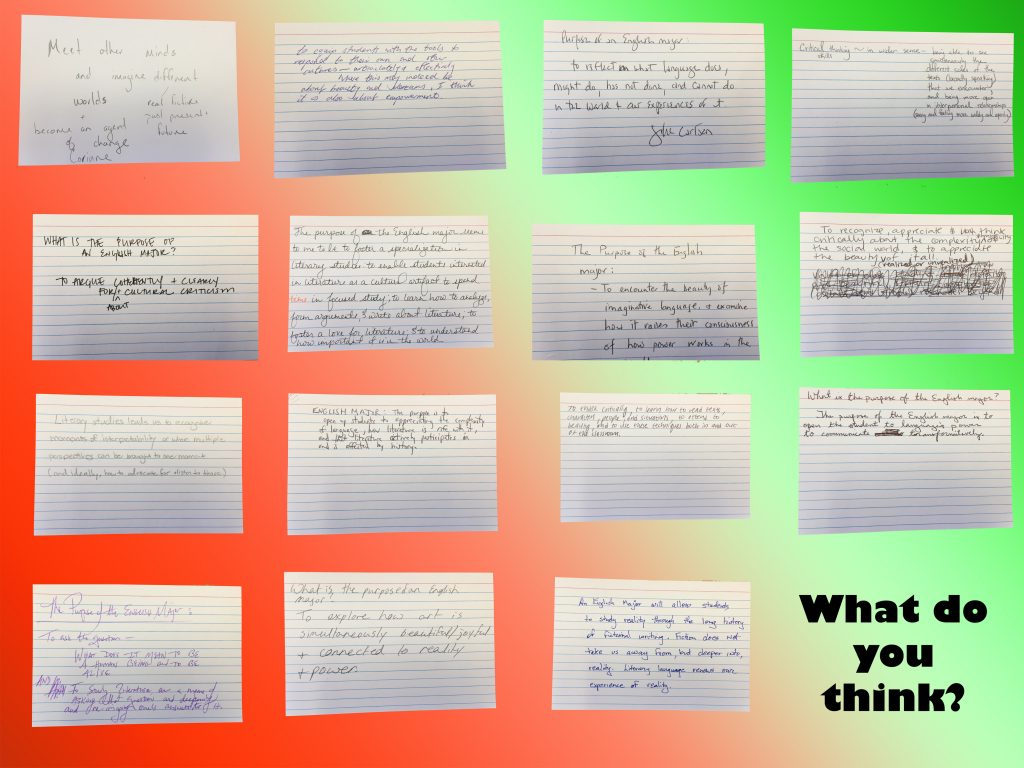

After our conversation, meeting participants wrote down their response to the question: what do you think is the purpose of the English major? A slideshow of our responses is at the top of this page, and you can see them in one image below!